Did steam eat the world?

Getting caught in “digital revolution” misses the point.

Marc Andreessen is famous for coining the phrase “software is eating the world.” The point: firms of all shapes and sizes are using technology to transform their business model and products. What people remembered? “Disruption is coming” “Uncertainty is everywhere” “Digital experiences are king.”

The buzz hasn’t stopped. Incumbent firms are acquiring start-ups at an astonishing rate and investing millions into “innovation labs.” The payoffs have been hit or miss.

Has it always been this way? Have previous generations hyped general technology? I was recently in Seattle, WA and walked past their beautiful Amtrak station. It prompted question: were people this psyched about steam?

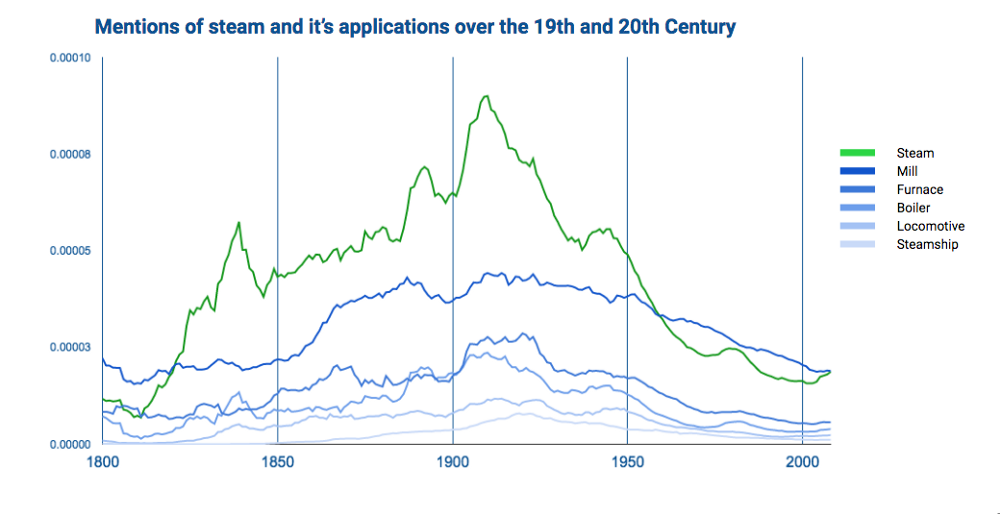

They were! Steam was a massive concept. Google has a great way to research the question. It’s called Ngrams and it counts the appearance of terms in publications going back hundreds of years. If someone was chatting about steam[fill in the blank] in a newspaper or book, we could find the relative frequency of that term. We’re talking about digging up 200-year old, tech-crowd chatter.

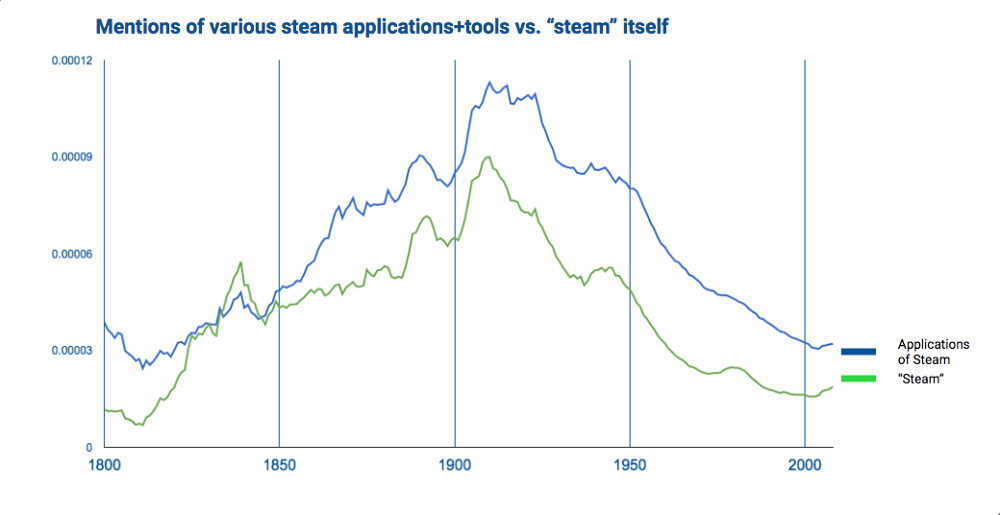

I compared mentions of “steam” to the major applications at the time: heating, manufacturing, transportation. Sure enough, like software today, the world heard more about “steam” than any of it’s individual, life-changing, applications. Steam ate the world — if you fall victim to a classic cognitive fallacy. Tversky and Koehler, behavioral economists, defined it as the subadditivity effect. That’s a fancy way of saying “you underestimate the meaning of something by giving it a single name.” When we bundle all technological progress under an umbrella like steam or software we tend to constrain our understanding of how those tools advance countries, markets, and people.

How do we combat this misperception? Well, we have to focus on the details. Rather than saying “steam is taking over the world” we should focus on hearing the case studies: “the locomotive has made it possible to travel the country in days, not weeks.” Technical progress becomes meaningful in those facts and realities.

Folks spoke about wheat mills and trains more than the underlying technology. It’s hard to see, or hear, that unless you take the time to aggregate all the places where steam power was applied to make an impact on the world. Steam didn’t eat the world. Cornelius Vanderbilt, Oliver Evans, and Robert Fulton “ate the world” with their respective dominations of the railroad, manufacturing, and steamship industries. The real impact of the steam engine is with those stories, not the technology itself.

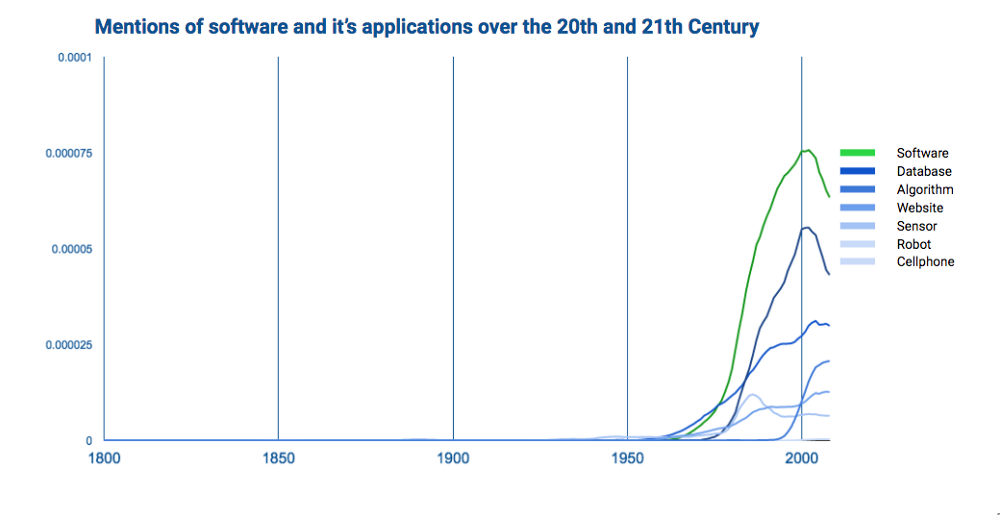

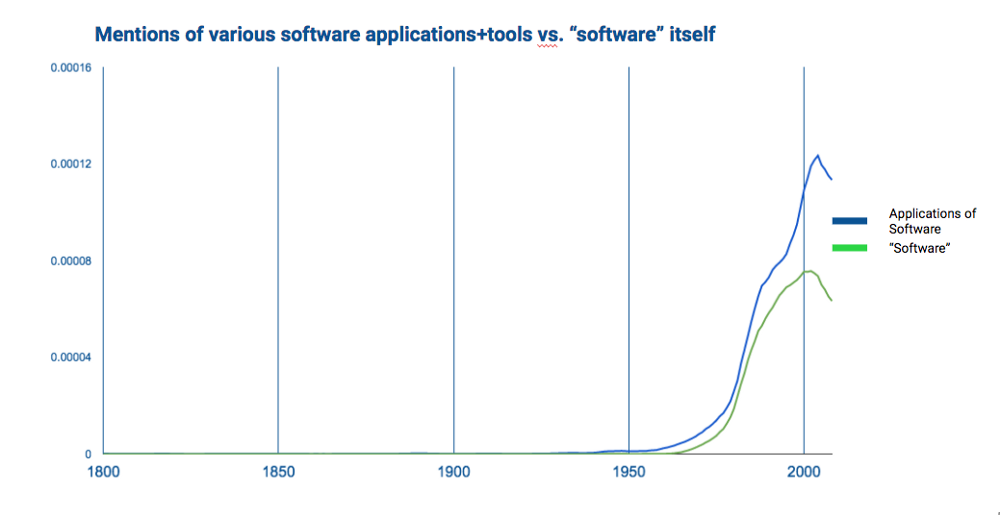

Flash forward 125 years. We see the same phenomenon today. I ran the same search with updated terms. Software and several applications: databases, algorithms, sensors, robots, cellphones, websites.

Software is a general tool with wide usage. It has the most references because it shares something in common with all the applications. It’s easy to get caught up in the term. Digital is another great example. What’s the point of digital unless we’re talking about the ability to share movements across the globe or automate busywork for doctors. The aggregate data proves the same point decades later. Folks are more interested in cellphones and sensors than just “software.” Again, hard to appreciate until we compile those examples.

The lesson for leadership teams: understand how software changes your fundamental business model. Andreessen tried to share this in the letter but failed to convey it with his catchphrase.

Software isn’t eating the world. Firms, leaders, and teams that use technology to change how they solve real problems “eat the world.”

Not as catchy, I guess!?

The average CEO isn’t responsible for developing the next, world-changing technology. James Watt, inventor of the steam engine, died in 1819 34 years before Vanderbilt’s New York Central Railroad was founded. It took decades after his passing for his invention to integrate into daily life.

Watt was an inventor, not a manager. In fact, he hated operating his small consulting business. The comparison between him and Vanderbilt isn’t to challenge their life choices or impact. It’s just important to know your aspirations as an organization before investing millions of dollars.

You have a company or a team with a purpose: to bring X product to Y people. Your job is to discover the most efficient, creative, beautiful way to produce and share your work. Investing in technology for technology’s sake — agile transformation, cloud devops, machine learning AI, etc. — can distract you from your core job: creating value for someone else.

The next time you find yourself saying “software is eating the world” or “we need digital experiences” or some combination of #bigdata #disruption… …just check yourself. Make sure you’re not blowing hot air.

Special thanks to Matt Nicklay for building and sharing his python app that grabs raw data from Ngrams queries.